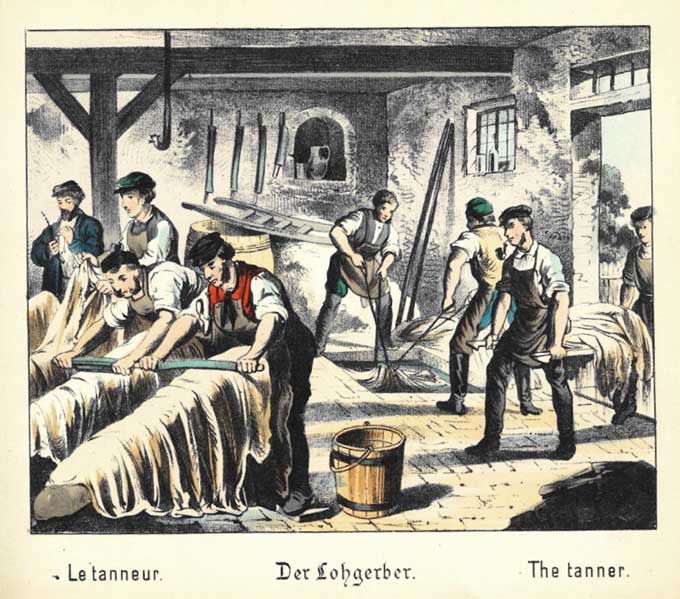

The Tanner

It was the common colonial trade of a tanner, an integral part of colonial village life. Tanning was the process of converting skins of cows, goats, calves, sheep, hogs, sheep, and dogs into raw hides and eventually leather. The demand for leather was great in America. Leather was used for buckskin britches, aprons made for blacksmiths, tops of carriages saddles and harnesses, shoes, boots, gloves, caps, and shot pouches for flintlock ammunition.

Many men including farmers tried their efforts on tanning by hollowing out logs and using them as vats. Although once a novice tanner ruins a hide or two, he was more than willing to divide the next hide with a tanner so that a leather hide or a boot that didn't crack was successfully produced.

Tanning from the Encyclopedia of Sciences, Arts and Trades, Diderot 1769

The tanner used every part of the animal once the hide was stripped. He sold the hair to the plasterer to use in holding lime-mortar together for walls, horse-hair plaster for the colonial homes. Offal or material remaining after the animal had been butchered was sold to peddlers who in turn sold it to gluemakers.

Nobody knows who developed the process of tanning since no records were kept. The Chinese, Babylonians, Assyrians, Sumerians and Egyptians used the basic tanning methods some two-thousand years prior to our forefathers in America.

The bark mill which was tanning's first mechanized accessory which used horsepower was used into the end of the 19th century. A tanbark mill was no more than a vertical post with a heavy pole attached to it which served as an axle tree for a thick stone wheel with corrugated edges. It was the corrugated edges that crushed the bark in a circular wooden trough

An illustration of a bark mill from Colonial Craftsmen and the Beginnings of American Industry, p. 33, author Edwin Tunis, 1965

During colonial tanning, each tanyard from New England to the southern states had the basic type of equipment - beaming sheds, tan vats, bark mills, and tools such as a the tanner's hook, fleshing knife, dehairing knife, spud for removing tanbark, skiver for splitting hides and skins, and the beam.

There was a series of tanning vats sunk to ground level which were six feet long, four feet deep, and from four to six feet wide and separated by walkways. Some cities granted tanners permission to put vats on their tanyard. In 1641, George Burden and James Everell were granted permission by the city of Boston "to sink a pit to water their leather" which was located near a millpond. However, if the odor was too annoying to the town folk, the tanners would have to fill up their vat. As the demand of vats grew town's would sink their own vats and rent them out to tanners for a period of seven years.

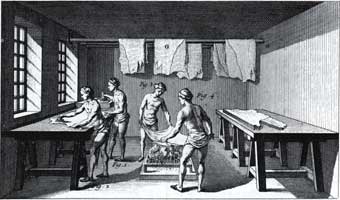

Hides being placed into vats containing lime solution. Encyclopedia of Sciences, Arts and Trades, Diderot 1769

The preliminary washing took about thirty hours, washing the hide free of dung, dirt, and blood in a stream, pond or even the ocean. Along the Massachusetts coast the raw hides were placed in vats that were sunk in the sand and soaked in sea water. A tanner by the name of Philemon Dickerson worked in 1630 at Blubber Hollow, a section of town in Salem, Massachusetts. He simply weighted his hides down with stones along the inlet and let the sea water do the softening.

After the preliminary washing, the hide was then placed hair down in a vat which contained a lime solution known as calcium hydroxide obtained from shells or limestone. The solution would burn the top hair layers of skin off. The hides would soak for a time based upon the thickness of the skin. In later years, tanners discovered that if they added sodium sulfide to pour as a soupy solution over the hide, they could avoid much scraping. Each vat after the first vat contained stronger solution.

The skins were removed and the bleached fat and hair-lime residue was scraped off and used for plastering walls. The process of removing the hair could take a year or more. In fact, the preamble to the acts of Edward VI which was written before 1553 stated that the hides had to remain in the vats for more than a year. However in the secret of darkness, some English tanners discovered how they could tan the hide within a month using "seething hot liquor with their oozes into their tan vats."

The hides were scraped free of the bulk of the hair using a slanting beam board with specialized two handled knives called fleshing knives. On the flesh side, fat and tissue were removed. On the grain side the hair and the epidermis were removed. The hide that was washed permeated with gelatin under the corium (the middle layer of the hide) which was then transformed into leather.

A thorough washing followed the scraping process. The hide was full of lime and swollen from the liming process. It was time to delime the hide using a bating process or dumping excrement over the hides. Using rotting scraps of hide, urine, feces or stale beer made the the air smell foul and pungent. But this stage treated the hides with enzymes usually found in the digestive system. Once recipe stated that fourteen quarts of dog dung were to be used for every four dozen skins. The bating technique truly worked. The hide was much softer and the skins were no longer rubbery.

The stacking of hides in pits between layers of tanbark was part of the tannin process. Encyclopedia of Sciences, Arts and Trades, Diderot 1769

Once the final step was finished the hides would be hung over drying lines made out of wooden poles. The leather hide was rather stiff and had to be softened without cracking or damaging the leather.

It was time for the currier to take over in making the leather pliable using items like a mixture of tallow and neat's foot oil. He alway worked in tandem with the tanner in the process. The French word for currier is corroyeur. Like the tanner, the currier used a beam to scrape away any addition flesh from wet leather hides. Oozes and liquor was used to keep the leather saturated. The currier would burnish the surface with an iron slicker and scouring stone. The more he burnished the surface, the the leather became thinner and softer. He would shave the leather into the correct thickness, beat and scrape the leather with oils, and introduce waxes, dyes, and fish oils in the process.

Curriers treating, shaving and burnishing hides. Encyclopedia of Sciences, Arts and Trades, Diderot 1769

Coenraet Ten Eyck, a successful shoe dealer, tanner, and manufacturer prospered as early as 1653 with his tan pits set up in marshy swamp known as the "Swamp" located on the west side of Broad street above Beaver Street in New Amsterdam. On this tract otherwise known as the "sheep pasture," another shoemaker and tanner, Abel Hardenbrook built his tan pits in 1661. Abel along wth Coenraet and others owned collectively a bark mill. It was due to the town expansion in 1676 that forced the the successful tanning business to fill up their vats and move elsewhere.

Governor Andros in August 1676 appointed two tanners for the entire city with Peter Pangborne being appointed currier for the city. It was the Bolting Act of 1676 that stated, "that no butcher be permitted to be currier, or shoemaker, or tanner; nor shall any tanner be either currier, shoemaker, or butcher, it being consonant to the laws of England and practice in the neighbour Colonys of the Massachusetts and Connecticott."

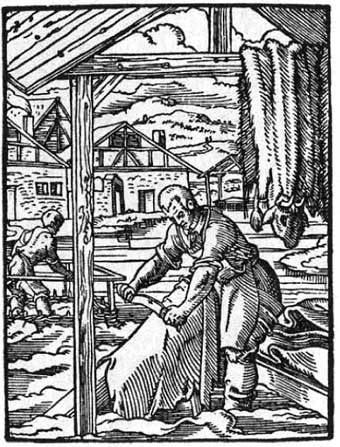

Hanns Richter 1609

The famous fur trader and land speculator, George Croghan, while living in Pennsboro, Pennsylvania in 1749 had a cluster of buildings along the Conondoguinit Creek. One of the buildings was a shop for tanning furs and another shop for storing the furs until a wagon load could be shipped to the hatters and feltmakers of Philadelphia. A deed found eight years after Croghan left Pennsylvania mentioned "houses, barns, stables, outhouses, edifices, buildings, tanyards, tan vatts, lime pitts, garden and other improvements."

Possibly the largest tannery in its day was established in Pennsylvania in Eastown, Chester County, now known as Paoli, by Captain Isaac Wayne who was "a man of great industry and enterprise." It was an extensive tannery which produced considerable profit for a number of years. Upon Isaac's death in 1774, his son Anthony ran the Waynesborough estate.

With the support of Benjamin Franklin, Anthony won a commission as colonel in a 4th Pennsylvania Battalion on January 4, 1776. During the Revolutionary War on February 21, 1777, Anthony was promoted to Brigadier General. After the war he was promoted to Major General.

Due to his involvement with George Washington and Lafayette and the battles of Brandywine and Germantown along with his encampment at Valley Forge, Anthony had to assign an agent to manage his tanning business at Waynesborough. At the termination of the war, the business had realized a net loss of £7000.

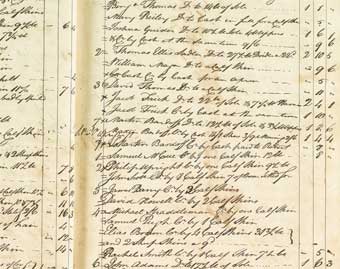

Major General Anthony Wayne's tannery business account book which sold at Pook and Pook April 26, 2014 for $7,200

Details of Wayne's account book

One of the most comprehensive visions of a tanner in colonial American can be found in extensive diary which was kept for sixty-five years by a New Hampshire farmer by the name of Samuel Lane. He was a successful tanner that traced his roots back to when he was nine when he learned shoemaking from his father. Here are some entries in his journal regarding the tanning profession:

June 16, 1741. my House was Raised. I Bro't Some Boards and Nails from Hampton wh I had Bo't there, and Clam Shells for Lime, Shingles &c to help build my House withal.

July 1, 1741. my Bark-House was Raised but not Covered till next year.

Other entries from 1741- I was pritty near out of Debt; but then I had worked up my Lether, and was pretty bare on't for Stock; but I work'd Some Lether for other People; & Some I Bo't &c. that I got along as well as I could. - and having taken some Hides this Winter, I wanted a Tanyard (Note. I have to tan this year 7 Hides which I hung up in my Chamber having no Barn) and last fall having made me a mean Water Pitt with Slabbs; I dare not put my hides in Soak Early, lest I should not get my Pitts ready timely for Liming: But the 8th of may 1742 I finished putting Down 2 Tanpits: and having no Bark-Mill, I carried my Bark that year, to mr Jewets to grind, and hired his Mill and Horse to grind it, which is Costly.

June 1. [1742] Bro't mother James over to See us. Being out of Lether this Summer, I was obliged to take out my new Lether as Soon as possible this fall 1742 a little undertand.

Oct 13, 1742. I Rais'd my Shop, and finished it as fast as I Co'd against Winter. I tan 23 Hides & 24 Calfskins this year.

Dec 6. [1742] Moved into my New Shop where I and my Wife lived Chiefly this Winter, to Save Wood. Note. this Shop Stood Against the West End of my House, at a Chimney of my House. Note. this Winter I having no Barn kept my Cow in my Bark-House. Note. about the end of the year 1741 & begining of 1742 & so on for Some years there are great Religious Commotions in the Land. Note. New Tenore Money 4 Double to ye other, began in 1742.

Apr 6, 1743. I Bo't a Barkstone of Saml Lovet of Hampton for 10-15-0 Delivered at my House, old Tenr.

June 1743. I put Down my Bark-Mill.

Oct 6, 1743 I Enter'd the 26th year of my Age. My principle Business is now my Trade; and the year 1732, I Tan'd 24 Hides & 18 Calfskins. Note. this year I hired an old England man to work wth me.

Oct 6, 1744. I Enter'd the 27th year of my Age. I Tan'd 18 Hides & 40 Skins this year.

Oct 6, 1745. I Enter'd ye 28th year of my Age in 1745, I Taned 15 Hides and about 50 Skins.

Oct 6, 1746. I Enter'd ye 29th year of my Age.

Note. Dollars are now about 24s old tenr apiece.

1746. I Taned 35 Hides and about 47 Calfskins.

Oct 6, 1747. I Enter'd the 30th year of my Age. this year I Taned 37 Hides and 63 Calfskins.

Oct 6, 1748. I Enter'd ye 31st year of my Age. this year I Taned 26 Hides and 55 Halfskins. as Money Sinks So verry fast, I am trying out Town as well as in Town, to lay it out in Land, but Can't Succeed to my mind.

Oct 6, 1749. I Enter'd ye 32d year of my Age. this year I tan 38 Hides and 83 Calfskins.

Oct 1. [1750] Anthony Pevy began to Dig my 2nd Well behind my House. Note. in 1749, by reason of the great Drought and Multitude of Cattle were killed and Hides fell again to 16d and so continued till about 1755, and those that run of the price lost by it.

Oct 6, 1750. I Enter'd ye 33rd year of my Age. this year I tan 55 Hides (&Sold Br Jno 3) and 36 Skins.

Oct 3. [1751] I sold my mare to my Father for 95£ old Tenr. about these years I measure abundance of Land. this year I Bo't a Right in Barnstead of my Br Wm. Note. Many people Several years past run up the price of Hides to 2s pr lb & Some more: after which Lether fell, and their Stock after it was tan't would not fetch hardly so much as they gave for the Hides.

Oct 6, 1751. I Enter'd the 34th year of my Age. this year I tan 28 Hides and 66 Skins.

Oct 17th, 1752. I Enter'd the 35th year of my Age. this year I tan 22 Hides and 75 Skins.

Oct 17, 1753. I Enter'd ye 36th year of my Age. this year I tan 25 Hides and 70 Skins.

Oct 17, 1754. I Enter'd ye 37th year of my Age. this year I tan 27 Hides 80 Calfskins & 63 Sheepskins.

Oct 17, 1755. I Enter'd ye 38th year of my Age. this year I Tan 38 Hides & 102 Calfskins.

Oct 17, 1756. I Enter'd the 39th year of my Age this year I Tan 49 Hides & 106 Calfskins.

Oct 17, 1757. I Enter'd the 40th year of my Age. this year I Tan 43 1/2 Hides and 140 Calfskins.

Oct 17, 1758. I Enter'd the 41st year of my Age. this year I Tan 57 Hides and 140 Calfskins, which is the Most that ever I Taned in a year.

Samuel Lane's Journal

The slow process of tanning was difficult manual labor and remained the same in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. By 1880 the introduction of substantial processing equipment and automation of the beam houses took the small scale tanning industry into large scale production. Chicago had in 1880 240 firms that tanned and finished leather goods with an average of 16 workers. WIth automation, a few large firms monopolized the tanning industry which eventually lead to an eventual decline in the tanning industry.

Whey you see colonial records with "tanner" beside an individual's name, you can appreciate more the true dedication and back-breaking work that the this colonial profession endured.

Source: Text and Research by Bryan Wright